Saturday, September 30, 2006

A Fresh Take on Masculinity

Thanks to my friend Ig (pictured above), I’ve recently completed reading the autobiography of world champion kickboxer Paul “Hurricane” Briggs.

Heart Soul Fire: The Journey of Paul Briggs not only traces Briggs’ rise in the kickboxing and boxing world, but also powerfully documents his transformation from drug addict and thug to mindful individual, dedicated husband and father, and inspiring public figure.

It was particularly refreshing to read that part of the book in which Briggs talks about his idea of starting a mentoring group to “give young blokes a different experience of what masculinity is”.

Notes Briggs: “The most common word used to describe what is manful – macho – is all about ego, nothing about depth of character. [ . . . ] Boys need to fathom that being a man is not about being aggressive, sexist, homophobic, emotionally mute, overconfident, and pig-headed. Such qualities have no business being used as reference points for manhood. We have evolved too much psychologically to allow boys to be so limited in their thoughts and feelings”.

Towards the end of his autobiography, Briggs returns to this theme, observing that, “[t]he reason I’m telling my story is not so people will glorify my ring exploits – it is for people to hear me. And by people I mean men. In a broader sense, beyond my own family’s welfare, I hope my achievements in the ring will prise open the stubborn minds of men to ideas I have about masculinity, to listen to me talk of valour, honour, and responsibility.

“I’d like to show them a fresh take on masculinity, one that is not rooted in physicality and ego but in vulnerability, self-love, and noble values. [ . . . ] The torrent of gung-ho, aggressive, and vacuous male role models steamrolls over qualities such as kindness and gentleness and caring. They are seen as weak, disdainfully feminine qualities a man should avoid like rattlesnakes. I say the opposite. I say women are lucky. Generally speaking, they are closer to their emotional centre of gravity. They seem to be born with an emotional maturity that men inherently lack. So unless we develop this asset ourselves, we will never acquire it. If men made the effort, they’d realize what powerful, enriching rewards are to be had by tapping into their emotional wisdom.”

“To do so,” says Briggs, “is to become more of a man, not less. I think one of the greatest gifts a man can give himself is to learn to understand and process his feelings”.

I’m grateful that Paul Briggs has not only come to such realizations, but that he is willing to share them through his writing and his numerous speaking engagements. Through such efforts, young men, like my friend Ig, himself a talented and aspiring kickboxer, get to hear and reflect upon the “emotional wisdom” Briggs has gained and which he so eloquently expresses.

Of course, it’s not that Ig’s wonderful family hasn’t always embodied such wisdom, but I think that, sometimes, before a young person can fully understand and appreciate such wisdom, they may need to hear it from others outside of their immediate family; from, for example, the sporting figures they admire and wish to emulate.

Ig told me that he wanted me to read Heart Soul Fire: The Journey of Paul Briggs so that I would understand not only Briggs’ journey, but also his own journey. That both young men have, in their own ways, come through difficult times and emerged wiser and more compassionate is something of which we can all be grateful and proud.

Like his brothers and, thankfully, so many of his generation, Ig is a straight young man comfortable with his sexuality and respectful of the sexuality of the gay people he knows. Of course, this is just one of the many “enriching rewards” which result from a “fresh take on masculinity”.

See also the related Wild Reed posts:

What a Man! – Ben Cohen

The Thorpedo’s “Difficult Decision”

Rockin’ with Maxwell

The Trouble with the Male Dancer

The Trouble with the Male Dancer (Part 2)

Learning from the East

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

The Inspiring Brigid McDonald

A number of my friends in the justice and peace movement back in Minnesota have been mentioned in a recent piece by Star Tribune columnist Nick Coleman.

A number of my friends in the justice and peace movement back in Minnesota have been mentioned in a recent piece by Star Tribune columnist Nick Coleman.Coleman’s September 19 column focused on Brigid McDonald, a Sister of St. Joseph of Carondelet (CSJ), an active member of Women Against Military Madness, and a dear friend of mine.

Brigid also serves with me on the board of CPCSM. While I’ve been in Australia awaiting the completion of my Green Card application process, Brigid has been taking care of the beautiful plant I received in May when I began the process of becoming a CSJ consociate.

Along with her three biological sisters, Rita, Kate, and Jane, who are also Sisters of St Joseph of Carondelet, Brigid is the subject of a documentary film entitled Four Sisters for Peace (“rated ‘R’ for rebellious”!).

Following is Nick Coleman’s column on the inspiring Brigid McDonald. Enjoy!

By Nick Coleman

Star Tribune (Minneapolis)

September 19, 2006

Sister Brigid McDonald dropped her heavy Irish sweater somewhere on the way to the Lake Street Bridge, where she was standing on the St. Paul side of the Mississippi River Tuesday, in a cold wind and a spitting rain.

I was worried about her.

Sister Brigid was without a sweater, she had been fasting since Sunday and she will be 74 next week. On these frail shoulders lay whatever slim hopes we still harbor for peace.

“They prepare for war when it's cold, so we have to prepare for peace come hell or high water,” Sister Brigid said. “We’ve had both.” She laughed, which is a good sign in a frozen septuagenarian who is not eating.

McDonald is one of about 30 dedicated peace workers who have fasted since Sunday and have stood vigil – in unseasonable cold – on the heights above the Mississippi River to witness for peace. It is a small thing, this witness in a world at war and in a country whose leaders seem hellbent on trying to salvage the bloody lies of Iraq by doubling the wager and gambling yet more blood on Iran.

Twenty-seven hundred dead Americans, many more dead Iraqis. A public opposed to the war (half think it was a mistake; 60 percent say it's being mishandled) but cowed into silence while the government recklessly “redefines” torture so that it can be done with impunity, in our names.

A lonely few speak out.

There was a small huddle of dissenters on the east end of the bridge yesterday, waving signs saying Stop The Killing. A surprising number of passing drivers honked in support. A few glared. An occasional twerp shouted, “Get a job!” which was funny in a stupid way, because these peace workers have labored hard all their lives and are dedicated now to trying to leave a better world than the one they found.

“This may be a ‘fast,’ but it's not that fast,” said Ward Brennan of Minneapolis, one of those hungering for peace who admitted he was looking forward to a potluck supper tonight to end the fast.

“The temptations are grave,” Sister Brigid added. “This morning I passed up some beautiful cookies.”

Cookies are close, peace is not. I'd have eaten the cookies.

“But we have hope,” said Marie Braun of Minneapolis, another of the hungering. “The Berlin Wall fell, Nelson Mandela was released. We’ve seen things that were unexpected. The unexpected can come again.”

Besides, said Barb Palmer, there have been eagles.

The peace vigil, normally held each Wednesday at 5 p.m., has gone all day this week, 9 to 5. The expanded hours have brought signs of approval from on high: beautiful eagles that have soared above the bridge, conveying symbolic approval on the peace workers below from the mighty symbol of a mighty troubled country.

“War is not the means to peace,” said Sister Brigid. “Any more than drinking is the means to sobriety.”

Yes. We are on a binge.

Yesterday, at the United Nations, President Bush accused Iran of squandering its wealth on weapons. The pot calling the kettle black. The U.S. has spent $320 billion in Iraq, $7 billion of that from Minnesota – more than $1,000 for every man, woman and child of us, plus all the squandered and wounded lives.

But no need to bother ourselves about that little war in Iraq or those little ladies standing in the cold and the wind on the bridge. Keep moving. Nothing happening here.

By the way, Thursday is the International Day of Peace, established by the United Nations in 1981 to bolster peace with vigils, prayers and moments of silence (a minute at noon) in a world where 1,000 people – many of them children – are killed each day.

We need a day like that.

The Irish poet Yeats said, “peace comes dropping slow.” Right now, that seems overly optimistic. But until Sister Brigid and her friends give up the fight, hope is alive.

Above: My parents met Brigid, and other friends of mine, when they visited Minnesota in July 2005. From left: Marilyn Schmidt; Betty McKenzie, CSJ; my mum, Margaret Bayly; Pepperwolf; and Brigid McDonald, CSJ.

Above: Gerry Sell; Darlene White; Bill Dumas; Brigid McDonald, CSJ; and Susan Olson – July 2005.

Above: In October 2004, while on a business trip to the US, my older brother, Chris, visited me in the Twin Cities. During his visit we went and heard award-winning independent journalist Amy Goodman speak at St. Joan of Arc Church. Standing from left: Brigid McDonald, CSJ; Jane McDonald, CSJ; me; Marie Braun; and Chris.

Monday, September 25, 2006

In the Garden of Spirituality: Rod Cameron

but to cultivate a flowering garden of life.”

- Pope John XXIII

Continuing a series of reflections on spirituality, I offer today the perspective of Australian writer and Catholic priest Rod Cameron OSA.

No exploration of human living could be complete without close attention to the world-wide experience of the Sacred. This experience has been central to every recorded culture.

But besides this general awareness of God there are special moments of insight that come to individuals and deeply affect their lives. These may be moments of awe and wonder when the individual feels as one with humanity or with the world. These are moments of peak experience.

It was the renowned psychologist, Abraham Maslow, who introduced the term “peak experience” into modern use. He saw how important it is for science to study the psychology of mentally healthy and alert people. Such research indirectly helps us to understand mental illness. We need to know what it means to be healthy.

In the course of his research he discovered the importance of the peak experience which commonly plays a key role in the lives of creative people who are really “alive”.

This experience may come at the sight of a sunset or a beautiful landscape. It can occur in the excitement of city lights or in the charm of a person. Sometimes it occurs in very ordinary circumstances when there is a sudden insight into the understanding of things. We cannot “bring it on”. It simply comes.

One important effect of the peak experience is that it gives a deep sense of belonging. The person feels as one with the land, with humanity, or God. The opposite of this deep sense of belonging is alienation.

We are not dealing here with rare mystical experiences reserved for great saints. We are dealing with normal, healthy people who have allowed these experiences to remain as influences on their lives. Research suggests that such peak experiences are very common.

- Excerpted from Karingal: A Search for Australian Spirituality by Rod Cameron OSA (St. Pauls, Homebush, 1995).

Image: Michael J. Bayly.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

Afternoon

In the Garden of Spirituality: Zainab Salbi

In the Garden of Spirituality: Daniel Helminiak

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Return to Wagga

Above from left: Mike, Bernie, Dom, Mim, Ig, me, and Collette.

Above: Raph, displaying obvious joy in seeing me again!

Above: Mike and Collette.

Above: Ig, a state champion Muay Thai kickboxer, is temporary out of the ring while he recovers from knee surgery.

During my previous visit to Wagga in July, I only saw Ig briefly due to the fact that he was working in Canberra. It was therefore good to catch up with him while he was home recovering from recent surgery on his knee. I shared with him and his siblings the movie, V for Vendetta, which we all enjoyed, while he, in turn, made sure he completed reading the autobiography of world champion kickboxer Paul “Hurricane” Briggs so that he could give it to me to read when I left Wagga to return to Port Macquarie. Like all the members of his family, Ig's a very thoughtful and generous person.

Above: Enjoying the warm spring weather with Bernie and Ig.

Above and below: Raph in the orchard where he had worked prior to his travelling overseas in 2004-2005.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts Travelin’ South (Part II) and Travelin’ South (Part III).

Friday, September 22, 2006

Goulburn Reunion

As I’ve mentioned in a number of previous posts, I taught at Sts. Peter and Paul Primary School in Goulburn from January 1988 to December 1993.

A few nights before the dinner at Sasso’s, Catholic historian and theologian, Paul Collins, spoke in Goulburn and shared his observation that “real leadership is not to be found among bishops and clergy” (many of whom have fallen prey to clericalism), but, more often than not, “in groups of principals and teachers dedicated to reflecting communal living, social justice, and a sense that life is more than ‘the mighty dollar’”.

My experiences within Catholicism tend to confirm this, and there certainly was something very special about my time at Sts. Peter and Paul’s.

The sense of community that was actively cultivated, the support and encouragement I experienced as a member of staff, and the many happy memories I have of the children I taught and the many interesting and creative activities we engaged in together, are all at the heart of my high regard of the school and all who have been and/or continue to be involved with it.

Above: Marion MacDonald and Louise Hobbs.

Above: Kathy Klem, Jane Booth, and Marg Larkham.

Above: During my six years at St. Peter and Paul’s, the wonderful Jacki Kruger served as assistant principal. She and the principal at that time, Mike McGowan, were both instrumental in providing me the guidance, support and freedom I needed so as to both trust and develop my creativity and effectiveness as a teacher. They, like so many of the staff, embodied dedication to the teaching/learning process and love for the children in their care.

Below: My last year at Sts. Peter and Paul’s was 1993. Following is the “5B” class photograph of 1993, along with the school’s staff photograph of that year.

Postscript: November 2006: My friend and colleague Jacki Kruger was recently honored by Sts. Peter and Paul's school, as the following article from the Goulburn Post documents.

Honors Mrs Kruger’s Work

By Louise Thrower

Goulburn Post

November 20, 2006

Jacki Kruger’s long association as a teacher at Ss Peter and Paul’s Primary School was honoured on Friday with a naming of one of three new classroom blocks after her.

For Mrs Kruger, whose teaching career at the school stretches back to the early 1970s, Ss Peter and Paul’s holds a special place in her heart.

“It just feels like home,” she said after Friday’s opening ceremony, as children flocked around to cuddle her.

“It’s lovely to be here. The school has just gone from strength to strength.”

Mrs Kruger still does relief teaching at the school, which dates back to 1954.

When she started, the school was known as Our Lady of Sorrows and was just a small timber building holding three classrooms for some 60 or 70 students. On Sundays, partitions were folded back and the building converted to a church for weekly Mass.

Now modern, brick classrooms accommodating some 350 children envelop that old structure.

On Friday, member for Hume Alby Schultz also officially opened the Cullinan block, honouring Bishop Cullinan, who helped spark the 1962 school strike to gain State funding for Catholic schools, and the Mercy block, recognising the Sisters of Mercy’s contribution.

Archbishop Mark Coleridge blessed the new building while children sang songs and raised the Australian flag on the school’s new flagpole.

Gavin Rowley builders completed the $743,000 project in a record 16 weeks, to a design by local architect Garry Dutaillis.

The Federal Government granted $451,000, the school community $150,000, and the Catholic Education Office $142,000. The State Government provided a $150,000 interest rate subsidy.

In his address to a large gathering of students, parents and teachers, Peter Clarke, planning and facilities manager with the Catholic Education Office said he could talk about the new buildings, but he preferred to focus on something else.

With so much emphasis on global warming and the need for conservation, only one school in the diocese was doing its utmost to save water.

Through waterless urinals, an underground water harvesting system, and other measures reduced average daily water use from 2440 litres a day to just 660 litres.

“Your concern for the environment and pursuit of conservation reflects a commitment to Goulburn and the broader community, and for that you should be thanked,” Mr Clark said.

Other guests at the ceremony were member for Burrinjunk Katrina Hodgkinson, Mayor Paul Stephenson, Senator Ursula Stephens, Jeff Yates from the Catholic Education Office, Garry Dutaillis, Gavin Rowley, and priests from Mary Queen of Apostles Parish.

Picture: Jacki with grandson Sol outside the new classroom block named in her honor.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

• Goulburn Revisited

• Goulburn Landmarks

• Paul Collins and Marilyn Hatton

• Remnants of a Past Life.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Paul Collins and Marilyn Hatton

Actually, he and his wife Marilyn Hatton, who serves as a co-convenor of Ordination for Catholic Women (OCW), were both speakers at a September 12 Spirituality in the Pub event in Goulburn.

The title of their talk was “Handing on the Faith to the Next Generation: Have We Been a Success or Failure?” Together, Paul and Marilyn made a very interesting and insightful presentation in responding to this important question.

They began their presentation by outlining “the current context,” one marked by rampant materialism; a “tendency to fundamentalist views in a depleted historical era”; a growing number of people more educated about and questioning of religious issues; and a Church leadership in crisis, in transition, and, in many ways, no longer leading in a Christ-like fashion but masking and distorting God’s love and wisdom.

Such a challenging context gives rise to some important questions for the Catholic Church, a major one being: How do we model and practice our faith?

Collins is particularly concerned that our liturgies often fail to mediate experiences of the transcendent, a sense of the sacred. He notes that for many young people, nature is the place to which they go so as to experience awe.

“We need to help young people experience a sense of the sacred [within the Catholic community],” says Collins, along with “a sense that this sacred reality beckons them to respond in both prayerful silence and action.”

Insisting that he was “anti-clericalism, not anti-clergy,” Collins suggested to the audience (numbering around forty) that “real leadership is not to be found among bishops and clergy” (many of whom have fallen prey to clericalism), but, more often than not, “in Catholic schools; in groups of principals and teachers dedicated to reflecting communal living, social justice, and a sense that life is more than ‘the mighty dollar.’”

They, along with Catholic families, are, says Collins, “creating the Catholic imagination,” which, like a filter, enables young people to imagine and see the world in a uniquely Catholic way.

As Collins points out, “Our faith is not just about feeling happy and being nice, but about a 2,000-year-old tradition.” Catholicism should “help young people place themselves in the flow of history and the world.”

Yet Collins, though a firm believer in “the tradition” of the Catholic faith, is not a “traditionalist,” a term that has come to mean someone fearful of and resistant to change.

“If there’s one constant in the Church,” says Collins, “it’s change.” That being said, he acknowledged a tension within the contemporary Church regarding “sorting out what is constant and permanent, and what is changing and needs to be changing.”

“Our Catholic tradition equips us with freedom of conscience and a striving for understanding,” noted Collins towards the end of his co-presentation.

All of which “allows us to be generous and flexible to whatever life presents,” added Hatton.

Both agreed that freedom of conscience is one of the most important aspects of our faith needed to be handed on.

And thankfully there are people like Paul Collins, Marilyn Hatton, and others working within the Church to ensure that this and other important aspects of our rich Catholic faith are identified, discussed, celebrated, embodied and, indeed, “handed on.”

Above from left: Jacki Kruger, Goulburn SIP co-coordinator; Marilyn Hatton; Pat Smith, principal of St. Joseph's Primary School; Paul Collins; and Michael Bayly, executive coordinator of the U.S.-based Catholic Pastoral Committee on Sexual Minorities – Goulburn , September 12, 2006.

Above from left: Jacki Kruger, Goulburn SIP co-coordinator; Marilyn Hatton; Pat Smith, principal of St. Joseph's Primary School; Paul Collins; and Michael Bayly, executive coordinator of the U.S.-based Catholic Pastoral Committee on Sexual Minorities – Goulburn , September 12, 2006.See also the Wild Reed posts:

• Goulburn Revisited

• Goulburn Landmarks

• Goulburn Reunion

Goulburn Landmarks

Above: For a century-and-a-half, Goulburn was one of the largest fine wool producing regions in the country, so much so that it was dubbed the “Wool Capital” of Australia. The Big Merino, a popular tourist landmark, reflects this aspect of Goulburn’s history.

Fifteen metres high and eighteen metres long, the Big Merino is a three storey structure housing a gift and souvenir shop, an educational display depicting the history of wool growing and the wool industry in Australia, and a platform where visitors can peer through the giant ram's eyes!

Above: The Cathedral Church of St. Saviour.

Designed by architect Edmund Blackett, St. Saviour’s Cathedral was built between 1874 and 1888. It is one of the finest examples of Blackett’s work, and one of the last great cathedrals of its style ever built.

The seat of the Anglican Bishop of Canberra/Goulburn, St. Saviour’s interior is one of the most richly decorated and finely finished churches in Australia.

The tower, with its 8 bells, was completed to Blackett’s design in 1988.

For my first four years in Goulburn I lived just behind St. Saviour's – on, appropriately enough, Church Street!

Goulburn is renowned for its numerous and well preserved historical buildings. The city displays a range of architectural styles – from the 1830s and ‘40s, through to the early-late Victorian period and the early twentieth century.

Pictured above is Goulburn’s majestic Court House, while below is the little cottage in Clifford Street that I lived in during the last two years in Goulburn (1992-1993).

Above and below: As Australia’s oldest inland city, Goulburn boasts many buildings that reflect the architecture and style of Australia’s colonial past. The building above is the Southern Star Inn, built in 1860.

Above: The Old Cathedral of Sts. Peter and Paul.

Goulburn’s Catholic cathedral is termed “old” because it is no longer the residence of a bishop. With the establishment of the Archdiocese of Canberra/Goulburn in the 1920s, the new archbishop’s residence was moved to Canberra.

Above: Perhaps Goulburn's most famous (and certainly most visible) landmark – the War Memorial atop Rocky Hill.

Built by public subscription in 1924 as a memorial to the men of Goulburn and district who served in the First World War, the stone tower that comprises the Goulburn War Memorial can be seen from miles around. At night, a powerful beacon of light from the top of the tower, sweeps through the darkness.

Raising 20 metres from its position atop Rocky Hill, the lookout gallery at the top of the tower offers panoramic views of Goulburn and the surrounding area.

A nearby museum houses a collection of military artifacts and personal items used by soldiers in the two world wars, and documents Goulburn’s association with and contributions to these conflicts.

See also the previous Wild Reed post:

Goulburn Revisited

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Beyond a PC Pope

Allen observes, for instance, that “any PR consultant would have told the pope that if he wanted to make a point about the relationship between faith and reason, he shouldn’t open up with a comparison between Islam and Christianity that would be widely understood as a criticism of Islam, suggesting that it’s irrational and prone to violence.”

“Yet,” says Allen, “that is precisely what Benedict did in his address to 1,500 students and faculty at the University of Regensburg . . . citing a 14th century dialogue between the Byzantine emperor Manuel II Paleologus and a learned Persian. News headlines immediately focused upon the Pope’s use of the term jihad and its implied swipe at Muslim-influenced terrorism, shaping up as something of a replay of the Danish cartoon controversy.”

Yet according to Allen, the Pope “brought up the dialogue between Paleologus and the Persian to make a different point. Under the influence of its Greek heritage . . . Christianity represents a decisive choice in favor of the rationality of God. While Muslims may stress God's majesty and absolute transcendence, Christians believe it would contradict God's nature to act irrationally. [The pope] argued that the Gospel of John spoke the last word on the biblical concept of God: In the beginning was the logos, usually translated as word, but it is also the Greek term for reason.”

An important aim of the Pope’s lecture, titled “Faith, Reason and the University: Memories and Reflections,” was, says Allen, to warn against “an artificial truncation of human reason in the West.” Reason, according to the Pope, cannot disregard theology and metaphysics. “Attempts to construct an ethic from the rules of evolution or from psychology and sociology, end up being simply inadequate,” argues the Pope.

Yet it can also be argued that when an ethical stance (such as the Church’s stance on homosexuality) is formulated without the ongoing input and insights of sciences such as psychology and sociology, it is equally inadequate.

As Joseph O’Leary has perceptively noted, “Church discourse on gay people is heavily reliant on dehumanising objectifications, referring constantly to ‘objectively disordered tendencies’ or ‘dispositions’ or ‘inclinations’ and to ‘objectively immoral acts’. When Vatican documents seek to give themselves an air of scientific respectability, as they tell gay people the ‘objective truth’ about their sexual identities, they parody the jargon of old-fashioned homophobic psychoanalysts, who had never learned to listen to their ‘patients’ or to let them speak from their own lived experience.”

“In these utterances there is no respect shown to the freedom and intelligence of the addressee’s moral conscience,” says O’Leary.

Such “utterances” imply that the Pope and the magisterium have “the Truth”, and that the task of the rest of us is to make sure our lives and relationships conform to this Truth. Such a model reflects a static notion of revelation. Truth has been revealed, once and for all. Our experiences of God, mediated through our lives and relationships, simply don’t count.

In his lecture the Pope condemned “positivistic reason,” and lamented the exclusion of “the divine from the universality of reason.”

“A reason which is deaf to the divine and which relegates religion into the realm of subcultures,” says the pope, “is incapable of entering into the dialogue of cultures.”

Yet the question has to be asked: Who is really being deaf to the presence of the divine within the contemporary Catholic Church and the wider world?

As O’Leary points out: “It is taken for granted [by the Vatican] that gay people have no moral insights of their own which could enrich and correct church tradition. Any questioning is dismissed a priori as stemming from an erroneous conscience, which is seen as having no right to express itself (whatever Vatican II may have said on the matter.)”

Clearly, the Pope’s “universality of reason” does not encompass or welcome the experiences and insights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgenger (LGBT) people.

Indeed, as British theologian James Allison has noted, in the eyes of the Vatican, LGBT people “are only a ‘they’ – objects referred to.”

Allison is convinced that this is not simply “a cosmetic failure” with regards various Vatican documents. Rather in the official view, LGBT people “are not, strictly speaking, reasonable subjects who might have something to say” on matters affecting them and the wider Church.

“We are not capable of being subjects by virtue of our having ‘come out’, our having come to regard being gay or lesbian as part of our lives to be welcomed,” says Allison. “The only ‘homosexual’ persons who might be subjects in such discourse are those who accept that their ‘inclination’is a ‘more or less strong tendency’ towards acts which are ‘intrinsically evil’, and must therefore itself be considered ‘objectively disordered’.

Doesn’t sound very reasonable, does it?

Of course, there are some commentators who think the Pope’s championing of what he calls “the universality of reason”, is really an attempt to promote his own reactionary ideology and agenda, one which, according to Peter Schwarz, constitutes “a broadside against the enlightenment”.

Of the German media’s coverage of the Pope’s visit to Bavaria, Schwarz is left to wonder: “What about the rights of the members of other churches and non-believers, who are made to feel thoroughly intimidated by the unrelenting propaganda offensive for the Catholic Church?”

“German state television has made a mockery of every journalistic principle by uncritically propagating feudal obscurantism and singing the praises of Benedict XVI,” says Schwarz. “[T]he two main German state television channels function as little more than subsidiaries of Radio Vatican, [and] are clearly violating the statutory independence of public broadcasting and the constitutional separation of church and state.”

This recent ruckus can be seen to serve as one more example of the need for religion to break free from various medieval and supernatural beliefs that presently stifle it. As Don Cupitt argues in his 1984 book, The Sea of Faith, a transformation is taking place and needs to take place: a transformation that will see Christianity practiced without dogma, as a spiritual path, an ethic, a way of giving life to all.

Although ultimately, there will always be a mystery dimension of life, one that neither science nor theology will ever be able to fully explain or articulate, the transformed Christianity which Cupitt and others foresee, will be open to the insights of all and will not fear being shaped by such insights or, for that matter, by the findings of science. Faith and reason will be in dialogue, not opposition.

Recently, I heard historian and theologian Paul Collins say that a true leader is someone who assists and takes people from a place they’re at to a place they want and need to be – with relative ease, encouragement, and joy. The Catholic Church is obviously in a period of transition, of transformation – as is the wider Christian community. My prayer is that Benedict XVI may yet prove to be a leader in such a journey.

Assuming such leadership does not mean that the Pope needs to become “PC”, just open to the voice of God in the experiences and insights of others.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

A Dangerous Medieval Contention

What the Vatican Can Learn from the X-Men

Casanova-inspired Reflections on Papal Power – at 30,000 ft.

Celebrating Our Sanctifying Truth

In Search of a Global Ethic

Reflections on the Primacy of Conscience

A Dangerous Medieval Conviction

During a lecture in Bavaria, the Pope quoted the words of the 14th-century Byzantine emperor Manuel II: “Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.”

The Pope’s choice of quotation, says Armstrong, reflects a “medieval cast of mind”. Furthermore, “coming on the heels of the Danish cartoon crisis, [the Pope’s] remarks were extremely dangerous. They will convince more Muslims that the west is incurably Islamophobic and engaged in a new crusade.”

Following is the full text of Armstrong’s commentary.

___________________________

We cannot afford to maintain these ancient prejudices against Islam

Karen Armstrong

The Guardian

September 18, 2006

The Pope's remarks were dangerous, and will convince many more Muslims that the west is incurably Islamophobic.

In the 12th century, Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny, initiated a dialogue with the Islamic world. “I approach you not with arms, but with words,” he wrote to the Muslims whom he imagined reading his book, “not with force, but with reason, not with hatred, but with love.”

Yet his treatise was entitled Summary of the Whole Heresy of the Diabolical Sect of the Saracens and segued repeatedly into spluttering intransigence. Words failed Peter when he contemplated the “bestial cruelty” of Islam, which, he claimed, had established itself by the sword. Was Muhammad a true prophet? “I shall be worse than a donkey if I agree,” he expostulated, “worse than cattle if I assent!”

Peter was writing at the time of the Crusades. Even when Christians were trying to be fair, their entrenched loathing of Islam made it impossible for them to approach it objectively. For Peter, Islam was so self-evidently evil that it did not seem to occur to him that the Muslims he approached with such “love” might be offended by his remarks. This medieval cast of mind is still alive and well.

Last week, Pope Benedict XVI quoted, without qualification and with apparent approval, the words of the 14th-century Byzantine emperor Manuel II: “Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached.”

The Vatican seemed bemused by the Muslim outrage occasioned by the Pope's words, claiming that the Holy Father had simply intended “to cultivate an attitude of respect and dialogue toward the other religions and cultures, and obviously also towards Islam”.

But the Pope’s good intentions seem far from obvious. Hatred of Islam is so ubiquitous and so deeply rooted in western culture that it brings together people who are usually at daggers drawn. Neither the Danish cartoonists, who published the offensive caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad last February, nor the Christian fundamentalists who have called him a paedophile and a terrorist, would ordinarily make common cause with the Pope; yet on the subject of Islam they are in full agreement.

Our Islamophobia dates back to the time of the Crusades, and is entwined with our chronic anti-semitism. Some of the first Crusaders began their journey to the Holy Land by massacring the Jewish communities along the Rhine valley; the Crusaders ended their campaign in 1099 by slaughtering some 30,000 Muslims and Jews in Jerusalem. It is always difficult to forgive people we know we have wronged. Thenceforth Jews and Muslims became the shadow-self of Christendom, the mirror image of everything that we hoped we were not – or feared that we were.

The fearful fantasies created by Europeans at this time endured for centuries and reveal a buried anxiety about Christian identity and behaviour. When the popes called for a Crusade to the Holy Land, Christians often persecuted the local Jewish communities: why march 3,000 miles to Palestine to liberate the tomb of Christ, and leave unscathed the people who had – or so the Crusaders mistakenly assumed – actually killed Jesus? Jews were believed to kill little children and mix their blood with the leavened bread of Passover: this “blood libel” regularly inspired pogroms in Europe, and the image of the Jew as the child slayer laid bare an almost Oedipal terror of the parent faith.

Jesus had told his followers to love their enemies, not to exterminate them. It was when the Christians of Europe were fighting brutal holy wars against Muslims in the Middle East that Islam first became known in the west as the religion of the sword. At this time, when the popes were trying to impose celibacy on the reluctant clergy, Muhammad was portrayed by the scholar monks of Europe as a lecher, and Islam condemned – with ill-concealed envy – as a faith that encouraged Muslims to indulge their basest sexual instincts. At a time when European social order was deeply hierarchical, despite the egalitarian message of the gospel, Islam was condemned for giving too much respect to women and other menials.

In a state of unhealthy denial, Christians were projecting subterranean disquiet about their activities on to the victims of the Crusades, creating fantastic enemies in their own image and likeness. This habit has persisted.

The Muslims who have objected so vociferously to the Pope's denigration of Islam have accused him of “hypocrisy”, pointing out that the Catholic church is ill-placed to condemn violent jihad when it has itself been guilty of unholy violence in crusades, persecutions and inquisitions and, under Pope Pius XII, tacitly condoned the Nazi Holocaust.

Pope Benedict delivered his controversial speech in Germany the day after the fifth anniversary of September 11. It is difficult to believe that his reference to an inherently violent strain in Islam was entirely accidental. He has, most unfortunately, withdrawn from the interfaith initiatives inaugurated by his predecessor, John Paul II, at a time when they are more desperately needed than ever. Coming on the heels of the Danish cartoon crisis, his remarks were extremely dangerous. They will convince more Muslims that the west is incurably Islamophobic and engaged in a new crusade.

We simply cannot afford this type of bigotry. The trouble is that too many people in the western world unconsciously share this prejudice, convinced that Islam and the Qur’an are addicted to violence. The 9/11 terrorists, who in fact violated essential Islamic principles, have confirmed this deep-rooted western perception and are seen as typical Muslims instead of the deviants they really were.

With disturbing regularity, this medieval conviction surfaces every time there is trouble in the Middle East. Yet until the 20th century, Islam was a far more tolerant and peaceful faith than Christianity. The Qur’an strictly forbids any coercion in religion and regards all rightly guided religion as coming from God; and despite the western belief to the contrary, Muslims did not impose their faith by the sword.

The early conquests in Persia and Byzantium after the Prophet’s death were inspired by political rather than religious aspirations. Until the middle of the eighth century, Jews and Christians in the Muslim empire were actively discouraged from conversion to Islam, as, according to Qur’anic teaching, they had received authentic revelations of their own.

The extremism and intolerance that have surfaced in the Muslim world in our own day are a response to intractable political problems – oil, Palestine, the occupation of Muslim lands, the prevelance of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East, and the west's perceived “double standards” – and not to an ingrained religious imperative.

But the old myth of Islam as a chronically violent faith persists, and surfaces at the most inappropriate moments. As one of the received ideas of the west, it seems well-nigh impossible to eradicate. Indeed, we may even be strengthening it by falling back into our old habits of projection. As we see the violence – In Iraq, Palestine, Lebanon – for which we bear a measure of responsibility, there is a temptation, perhaps, to blame it all on “Islam”. But if we are feeding our prejudice in this way, we do so at our peril.

Karen Armstrong is the author of Islam: A Short History.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

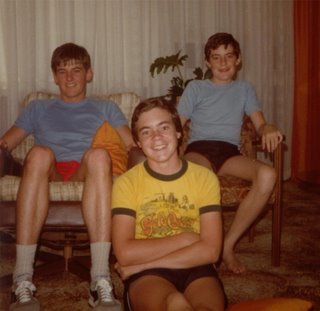

One of These Boys . . .

The picture above shows me with my two sport-playing brothers in 1976.

Mum’s been recently sorting through many of the old family photo albums and when I saw this particular shot, I joked with my younger brother about how, in retrospect, it’s pretty clear to see which of the three Bayly brothers would eventually come out as gay.

Not long after we laughed about this photo, the current affairs program Sixty Minutes featured a segment focusing on the possible causes of homosexuality and how parents can recognize a child is gay.

One of the researchers interviewed was Dr. Michael Bailey (how weird is that?) who maintains that the cause of homosexuality is still unknown, but that it’s most likely to be a combination of genetics and hormones. A child’s environment, i.e. the way he/she is raised, plays no part.

Well, I could have told him that, as could most gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender (GLBT) people who grew up with siblings who shared their environment but who didn’t end up queer. It seems such a no-brainer to me, and yet in the U.S. there remains a powerful movement preaching the message that homosexuality is a choice and offering “therapies” to “change” gay people. Of course, the facts say otherwise.

Anyway, here are a few more images from the archives.

Above: Here I am with Deano, our family’s yellow Labrador, sitting under the big jacaranda tree in our backyard. This photo was probably around 1980. We had just come back from swimming in the Namoi River, something my brothers and I loved to do with Deano during the hot, dry Australian summers.

I remember how I would pretend to be drowning and call out to Deano. Without fail, he would always jump into the water and swim out to me. I’d grab hold of his collar and he’d drag me back to shore. He was a great dog. Sadly, he passed away in 1986.

Above: The Bayly boys – Chris, Tim, and Michael – photographed in the early 1980s.

Above: With my older brother Chris and our Great Aunt Phyllis (1913-1996), photographed in the late 1960s.

Above: Me with my younger brother, Tim, in the backyard of our home at 23 Beulah St., Gunnedah. This photo was taken in 1970.

I remember how, years later, Aunty Phyllis would look at photos like this one and the one above it, and remark, with a smile, that my brothers and I looked like “little kings.”

Above: My brothers and I in 1976 with my Dad’s grandmother, Emily Simmons (1892 – 1982) – known to the family as Gran. Don’t let her frail demure fool you. She could play a mean game of Snap!

Above: My brothers and I with our grandmothers in 1991. From left: Chris; our maternal grandmother, Olive Sparkes (1906-1997); me; our paternal grandmother, Belle Smith (1919-2005); and Tim.

Nanna Smith and Aunty Phyllis were sisters. Their mother was Gran. Both Aunty Phyllis and Gran are pictured in previous photos.

Above: With an outfit like this, I guess it was inevitable that I’d one day live in the United States!

I find it interesting that in this photograph I’m standing in front of a plant growing on a trellis, as this has become for me a metaphor for my relationship with the Catholic Church.

I see the Catholic tradition and my upbringing in it, as being like a trellis. It has grounded me and given me guidance as I, like a plant, have grown and blossomed.

Yet just as a plant, in its reaching for the sun, often extends beyond the framework of a trellis, I, like many Catholics, have stretched out beyond the anchoring framework of Catholicism while still remaining a part of this particular tradition and still being, in many ways, supported and encouraged by it.

I think that’s how religion should work. It shouldn’t restrict and hamper one’s spiritual growth but give us that initial push and ongoing guidance towards the source of life that births and sustains us – a source that cannot be contained by any one religious tradition; a source which is ultimately beyond all religious structures.

This has been my experience and truth as a spiritual seeker within the Catholic tradition. And I think it’s been many others’ as well.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts:

A Lesson from Play School

Those Europeans Are at it Again

Catholic Rainbow (Australian) Parents

The Bayly Family (Part I)

The Bayly Family (Part II)

The Bayly Family (Part III)

My Brother, the Drummer

A Rabbit’s Tale

A Not So “New” Catholic University

Recently, Catholic blogger Clayton Emmer posted an interview he conducted with the founder of the university, Derry Connolly, on his blogsite, The Weight of Glory.

It’s a very interesting interview, especially when Clayton inquires about faith formation and the place of academic freedom in the vision of this new Catholic university.

According to Connolly, the theology faculty “must be highly visible Catholic spokespersons” and “align themselves with the Church on issues facing people in the media and in technology in the community.”

Furthermore, “If they want to end up as chair of the philosophy department at Notre Dame, they shouldn’t come to John Paul the Great Catholic University, because we’re not going to allow them to do that type of academic research". (Does he mean critical and credible research?)

The faculty, in short, “needs to be steeped in the fundamentals of the Catholic faith and in Sacred Scripture”, noting that in the writings of Pope John Paul II, “there’s always a scriptural basis for his teaching.”

Does such an emphasis on “scriptural basis” mean that Intelligent Design theory will be taught in the university’s science department? That question was never posed to Connolly.

Indeed, Clayton missed a number of opportunities to engage Connolly on several important issues facing not only Catholic higher education, but the Catholic Church in general.

For instance, Connolly is adamant that at John Paul the Great Catholic University, “faculty cannot take positions that are at odds with the teachings of the Church.” He likens faculty at his university to baseball players at “home plate” where there are “definite boundaries.”

Freedom, apparently, is relegated to the “outfield.” “There are a million things people can go do which are not inconsistent with the teachings of the Church. Just play on [the outfield],” says Connolly. “Academic freedom at our university means you need to follow the rules . . .”

Clearly, faculty with questioning or dissenting views will not be welcome. Faculty – and theology faculty in particular – are to serve as stenographers for the Vatican. What a betrayal of Catholicism’s rich intellectual heritage!

Ironically, Clayton posted his interview at a time when in Iran, the ruling fundamentalist Islamic president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, is calling for a purge of “liberal and secular” academics.

I would like to ask Connolly how his university’s policy on strict adherence to church doctrine and the banning of any critical examination and questioning of such doctrine, differs from Ahmadinejad’s desire to crack down on “liberal” thinkers and teachers in Iranian universities.

Building on this, is Connolly aware of and/or interested in identifying any points of connection between the various forms of religious fundamentalism present in the world today?

What does he make, for instance, of Charles Hinton’s contention that “the one force that binds together all forms of fundamentalist religion is their adherence to patriarchy?”

It’s also a pity that Clayton didn’t challenge Connolly on his narrow and limited understanding of Church. Clearly, Connolly views the Church as, in the words of Catholic columnist and author Chris McGillion, “a kind of club with an inflexible set of rules, to which all its members must subscribe. Those who don’t [ . . . ] are made to feel unwelcome; those who question the rules are asked to leave or forced to go.”

Yet does this “kind of club” reflect the example of community modeled by Jesus?

Is it the only way to view and understand the reality of Church? Is it even an appropriate way to understand Church?

What are other ways present in our Catholic tradition and experience?

Are some of these more equipped than others to emulate Jesus and thus invite and encourage people to flourish, both individually and communally?

Unfortunately, Connolly’s new university isn’t really that new when it comes to its reactionary perspectives on life’s complexities and its narrow understanding of Catholicism.

As David Landry, an associate professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, has noted, “Catholic schools across the country run the spectrum. There are schools like Ava Maria [where], for example, if you’re ever divorced, you can’t work there. And if you get divorced, you’re fired. Thomas Aquinas College in California requires all faculty and staff to make an oath of fidelity [ . . . ] that you’ll never dissent from a single one of the Catholic Church’s teaching.”

At the other end of the spectrum are Catholic institutions like Georgetown, the Jesuit university that has extended health care and other benefits to employees’ domestic partners.

“Georgetown, Boston College, Holy Cross, Loyola, Dayton, Marquette, San Francisco, Santa Clara – these are schools that are on the other side of the spectrum,” says Landry.

“And [ . . . ] if you think about [all these] schools, where's the quality, where's the reputation? [ . . .] Well, Marquette has a natinal reputation, and Boston College does, and Georgetown.”

Will Connolly’s John Paul the Great Catholic University achieve such renown?

Well, it’s clear from Clayton’s interview, that Connolly doesn’t want his university to be in the same league as, say, Georgetown. Such institutions don’t pass muster to be part of “the club”.

Connolly would rather aspire to the Franciscan University of Steubenville, noting that “we’ve hired staff who graduated from Steubenville . . . guys who are young, can connect with kids, are on fire for their faith.” Steubenville was also instrumental in Connolly’s own faith formation. He notes in the interview that his first day at the Franciscan university “changed my life.”

Yet according to Landry and others, Steubenville, along with institutions like Ave Maria and St. Thomas Aquinas College, don't have a national reputation as centers of higher education and “never will because of their rigidity and their insistence on [a] pure enclave mentality.”

Here’s hoping that John Paul the Great Catholic University breaks free from such a mentality and gets to both experience and share the richness of the Catholic tradition – a tradition that, as another great pope, John XXIII, reminds us, is more about “cultivating a flowering garden of life” than it is “guarding a museum” . . . or a club.

Saturday, September 09, 2006

John le Carré’s Dark Suspicions

Recently, le Carré gave an interview to Danish journalist Jesper Stein Larsen in which he discussed not only his forthcoming novel, The Mission Song – which focuses on the exploitation of Congo by transnationals – but his views of the U.S. role in world affairs.

Following is an excerpt from this interview.

“We Have to Understand”

An Interview with John le Carré

Jesper Stein Larsen: Congo is [ . . . ] a part of the story. You're fascinated with that country.

John le Carré: Yes. I chose Congo because I am fascinated by losers. I like stories about underdogs. And Congo is the biggest loser of them all.

. . . East Congo, where part of the story takes place, has been particularly poorly treated for centuries. It's a rent-a-battlefield for everyone else, and they've just been screwed every time. There are only 30 miles of paved roads in Congo, but the country's minerals, diamonds and gold are worth billions. It's unlike any other trouble spot I've been to.

Jesper Stein Larsen: I get the impression that in your later books the style has become more associative and lyrical, yet your message has become stronger, angrier and more direct. Why's that?

John le Carré: I hope that both are true. Of course a lot of people will call it age rage and radicalism, but we are living in a time where political varieties and nuances are being reduced to terrifying simplifications. I read today that Bush said in a speech that if we let the war in Iraq go against us and bring our people home, they will come here to find us in America. I mean, this completely overlooks the fact that Iraq has nothing to do with terror. And yet by endless repetition and by the supine, disgraceful attitude of the American corporate media, these lies are entering into the perception of ordinary people. What we are seeing is an informational takeover by the U.S. on a terrible scale.

I'm one of those types who believe that we should continue to look at the objective facts. We need to find out where all these people are coming from and what they want. We shouldn't say, “all terrorists are the same,” or “all terrorists are mad,” because all forms of terrorism have – not an excuse, but a reason, and if we are going to do anything other than make war, we have to understand those reasons. The war against terror is a very difficult war against an ideology, but the U.S. has turned it into a territorial war.

Jesper Stein Larsen: What do you mean by that?

John le Carré: The most recent and awful example we've seen is Lebanon. If you kill one terrorist and 100 civilians, are you further away from terror or nearer? Not only have you created a future base for more terrorists, you've also created a hinterland – huge masses give themselves over as a logistical system of support for terror. If you go on inflaming Muslim sensitivities, you will actually convert people against you. And you will create the enemy you deserve [ . . . ] You don't accomplish anything if you abandon your democratic principles. You've got to be able to take losses. The logic the Americans are pursuing at the moment would have required us to bomb Dublin when the IRA attacked us. It's completely nuts.

Jesper Stein Larsen: How do you explain this?

John le Carré: My own dark suspicion is that the neoconservatives in the U.S. – the powerful and secretive few that they are – actually believe that they can use these kind of provocations to homogenize the Islamic threat, bring everybody forward, radicalize them, and then bomb the hell out of them.

Jesper Stein Larsen: In the old days, it was the conflict between the Cold War superpowers that threatened the life of the individual. Today, it's the transnational corporation that plays a big role in your books. Why's that?

John le Carré: Corporate power has been part of several of my later books, because it creates an aura of something so large, unaccountable and incomprehensible that you don't think you can do something as an individual. The enemy is indefinable. They are giant organizations with one foot in Liechtenstein and the other in the Netherlands Antilles, who hold their board meetings in England. And when you know that Tony Blair is more concerned about the opinion of Rupert Murdoch than about what his electorate thinks, you do worry.

I see an erosion of nationhood and democracy exactly as Mussolini described it. He said: “Democracy ends and fascism begins where political power and corporate power are inseparable.” You could have added religious and press power to that list. All four are at the fingertips of the right wing in the U.S.

Jesper Stein Larsen is a reporter for the Culture section of the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten.

Photo from Faces of Resistance by Michael Bayly.

Friday, September 08, 2006

In the Garden of Spirituality: Daniel Helminiak

but to cultivate a flowering garden of life.”

- Pope John XXIII

Continuing with a series of reflections on spirituality, I offer today the perspective of psychotherapist, theologian and author Daniel Helminiak.

When I say spiritual, I do not necessarily suggest any reference to religious faith, to God, or to Christ. I refer to something that is simply human, something in human experience that goes beyond the here and now. We have in us an opening to a beyond. That something is spiritual.

Different people might experience their spiritual nature in different ways – watching the stars at night, listening to a symphony, working through an intellectual problem, making love. A dimension to human experience exists that pulls us out of ourselves and lets us know that we, our very selves, are caught up in something that is vast and marvellous. We are bigger than ourselves. We are naturally self-transcending.

[All experiences that] move us beyond ourselves [ . . . ] are self-transcending experiences. All open us up to reality that is clearly not limited to the sensible, the concrete, the physical, the here and now. These experiences open us up to what is potentially universal and eternal. Through such experiences we move beyond ourselves, and more and more we ourselves become that beyond toward which we move. These are spiritual experiences.

- Excerpted from Daniel Helminiak’s book, Sex and the Sacred: Gay Identity and Spiritual Growth (Haworth Press, New York, 2006).

Image: Gordon Bayly.

See also the previous Wild Reed post:

In the Garden of Spirituality: Zainab Salbi

Thursday, September 07, 2006

Let’s Also Honor the “Expendables”

Without doubt, such documentaries serve as important historical testimonies to events which, in many ways, were life-changing for both individuals and societies.

Yet the selective choosing of what exactly is focused upon by many of these documentaries is troubling to me.

Yes, I want to hear the stories of loss and bravery, sacrifice and heartache from New York on September 11, 2001. Yet I also want to hear about, for example, the lives and stories of the citizens of Fallujah during the U.S. military's siege of this particular Iraqi city.

Why are some voices given a platform and packaged in sleek, high-tech productions for commercial consumption, while other voices are discounted, ignored, and even denied?

Renowned journalist, author, and filmmaker, John Pilger, offers an explanation by contending that for so-called first world countries to maintain their colonial assumptions, “millions of people [must] remain invisible and expendable.” And it’s these countries, with their often unconscious “colonial assumptions” which set the agenda for “mainstream” news and entertainment, and thus the focus of various types of documentaries.

In the introduction to his 2006 book, Freedom Next Time, Pilger observes that, “On March 28, 2003, during the attack on Iraq, sixty-two people were killed by an American missile that exploded in the al-Shula district of Baghdad. That evening, Newsnight, the BBC’s only regular televised current affairs programme, devoted forty-five seconds to the massacre – less than one second per death. Contrast that with July 7, 2005, when the terrorist bombing of London killed almost the same number of people and received such coverage that overnight we became intimate with the lives of the victims, and could mourn their loss or salute their courage.”

“In other words,” continues Pilger, “for the men, women and children blown to pieces in Baghdad, the solidarity we extended naturally to the London victims was denied; we were not allowed to know them. [ . . . ] Their violent extinction caused not a ripple in that man-made phenomenon known as the ‘mainstream’, the main source of what we call news. [ . . . ] The innocent people killed in London were worthy victims. The innocent people killed in Iraq were unworthy victims. Put another way, the London massacre was worthy of our compassion; the Iraqi outrages were not.”

Thankfully, there are people like John Pilger, Amy Goodman, and many others, who are working to provide forums for the voices of those considered as “not us”, and thus as “expendable” by those who view others’ usefulness only in terms of “our interests”.

And thankfully, too, more and more people are recognizing the limitations of the corporate “mainstream” media and turning to alternative, independent sources for news and information – sources which remind us that . . .

John Pilger’s book Freedom Next Time is published by Bantam Press.

Photo of Minneapolis writer and activist Carol Masters from Faces of Resistance by Michael Bayly.

See also the previous Wild Reed posts The Exception to the Rulers and Taking on Friedman.